Originally posted at: https://www.thedartmouth.com/article/2024/02/college-to-reinstate-standardized-test-requirement-for-class-of-2029

By Kelsey Wang

Published February 5, 2024

Dartmouth will reinstate the standardized test requirement for applicants to the Class of 2029 and beyond, according to a campus-wide email from President Sian Leah Beilock. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dartmouth adopted a test-optional policy for applicants to the Classes of 2025, 2026 and 2027 and a test-recommended policy for applicants to the Class of 2028, according to Lee Coffin, Vice President and Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid.

“The reactivation [of the test-required policy] has been modeled on a very comprehensive research study by a group of faculty,” Coffin said in an interview with The Dartmouth.

According to Coffin, the research group — which consisted of economics professors Elizabeth Cascio, Bruce Sacerdote ’90, Douglas Staiger and sociology professor Michele Tine — shared their findings with Coffin and Beilock in early December 2023. The group’s findings were also published in an article in the New York Times last month.

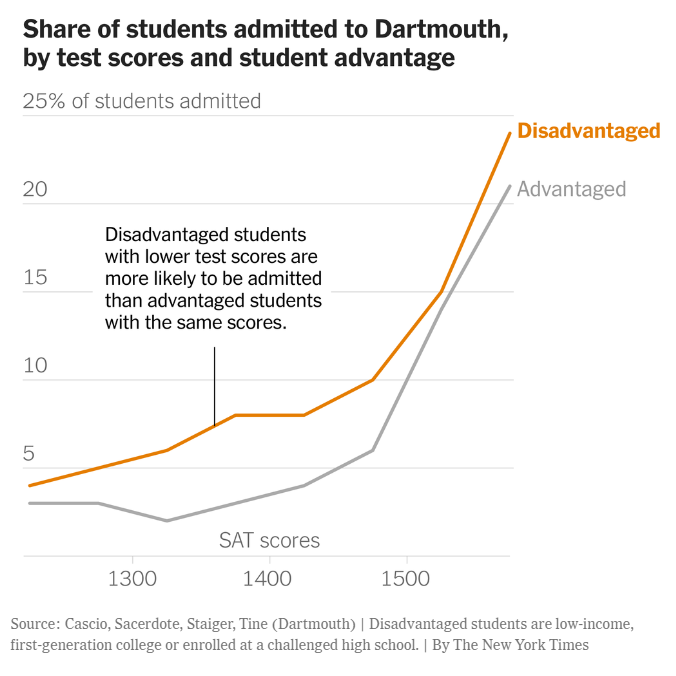

The faculty research group concluded that “standardized test scores are an important predictor of a student’s success in Dartmouth’s curriculum” regardless of a “student’s background or family income,” according to Beilock’s email.

According to Sacerdote, test scores are a useful way for admissions officers to identify high achieving students “particularly if they’re at a high school where admissions has … less information about the high school and therefore less information about the transcript.”

“We’re getting more and more applications from all around the world, and so in order to find high achieving students, test scores turn out to be a really helpful tool,” Sacerdote said. “Our analysis shows that we potentially miss out on some great applicants when we don’t have [test scores].”

The research group observed that there were certain cases where applicants did not submit their scores when the scores could have “helped that student tremendously, maybe tripling their chance of admissions,” according to Sacerdote.

Sacerdote also addressed the issue of equity in standardized testing and emphasized that Dartmouth admissions officers evaluate test scores in the context of the applicant.

Beilock wrote that the test-optional policy “disadvantages applicants from less-resourced families” who might choose to not submit their test scores because admissions officers evaluate their scores “in relation to local norms of their high school.”

“For a long time, Dartmouth has always practiced holistic admissions,” Sacerdote said. “That means that even when test scores are examined and used in the process, they’re examined very much in the framing of the environment that the applicant is coming from. [Coffin’s] team is keenly aware of the level of advantage or lack of advantage, both at the neighborhood level and at the high school level.”

Coffin added that the admissions team looks at the college-going rates, test scores and demographics of an applicant’s high school and evaluates the applicant’s test scores in that context.

“Your school profile says, ‘Our average score is x,’ and then we look at your score and we say, ‘Is it x-plus or x-minus?’” Coffin said. “The higher you are over that x, the more value that score has in the way we read it as an element of admissions. So, the question about low income or high income in some ways doesn’t matter because we’re going school by school.”

The admissions team also recognizes that different communities have varied access to test preparation, according to Coffin.

“That’s why testing is so helpful to less advantaged students because when admissions sees, ‘Wow, this student is really excelling in a less than perfect environment,’ that can be a very strong signal for that candidate,” Sacerdote added.

Coffin emphasized the results of the faculty research study are specific to Dartmouth and are not a “grander statement about higher-ed across the United States.”

“I lead an admission process that has to evaluate 30,000 plus people for 1,200 seats — what’s the best way to do that?” Coffin said. “Holistically, [GPAs and extracurriculars] matter. They always have, they always will.”

However, GPAs — which assumed more importance while the test-optional policy was in effect — are not sufficient data points for the admissions team, according to Coffin.

“Social science has a concept called the ceiling effect,” Coffin said. “When you plot people in a curve, there’s a cluster at the top of the curve. That’s our applicant pool. Most of the people who apply to Dartmouth are straight A students.”

Coffin said that contextualized testing is an additional data point that can help admissions officers “start to separate out this surplus of ability” and “make more precise decisions” as they review essays, extracurriculars and teacher recommendations.

“It’s not one or the other,” Coffin said. “It’s both [grades and test scores] together [that] help us make really strong decisions when we admit rates in the single digits.”

Beilock wrote that a test score “doesn’t — and shouldn’t — dictate [Dartmouth’s] admissions decisions” but should “inform” those decisions.

According to Coffin, around 52% of the applicants who applied to the three test-optional classes opted to submit their applications with a standardized test score, while two thirds of the students who eventually enrolled submitted test scores.

“Even in this optional space, the majority of the students at Dartmouth have applied and been admitted and enrolled with testing as part of their file,” Coffin said.

Coffin predicted that the reinstatement of the test-required policy might lead to a smaller applicant pool following several years of record-breaking numbers of applications. However, he also attributed some of the growth in applications to need-blind admissions for international students, the elimination of loans, the return of in-person outreach and the continuation of digital outreach adopted during the pandemic.

“All of these things contribute to the growth,” Coffin said. “Optional testing was some of it. I would be sad as the Dean of Admissions if people were applying to Dartmouth only because we’re test-optional.”

Other institutions are also considering a return to test-required admissions, according to Coffin.

“All of our peer schools are studying it, as we just did,” Coffin said. “I think the question is a really straightforward one: Does the college see an opportunity from the inclusion of more data in the application? And if the answer is no, you don’t need the SAT.”

Coffin said that the decision to return to the test-required policy was informed by conversations with Beilock, the Board of Trustees, the Council on Institutional Priorities, “all of the faculty committees that have some connection to either admission policy or instruction,” alumni groups and Dartmouth Student Government leadership. Coffin also reached out to a couple of guidance counselors to “seek their input.”

While Coffin said that he views the reinstatement of the testing requirement as “business as usual, with new information guiding us,” he acknowledged that “the critics of standardized testing will likely critique this decision in a way that they’re entitled to.”

“I think people outside of Dartmouth may have stronger reactions, but at the end of the day, I work for Dartmouth College, and my responsibility is to lead an admission process for Dartmouth that brings the best students from as many places as I can who are prepared to be successful in our curriculum,” Coffin said.